Do COVID-19 Lockdowns Reduce Healthcare Equity in Robust Systems?

By Alyce Dean

Considered two of the most successful healthcare systems globally, albeit, for different reasons, Sweden and Singapore have chosen dramatically different approaches when it comes to the COVID-19 response. Sweden, with their universal government-funded healthcare with equitable emphasis, have chosen a more relaxed approach opting out of strict lockdowns. Whereas Singapore, with their GDP efficient hybrid universal healthcare model, have chosen to include strict lockdown measures in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Both health systems look good on paper, but what are the real impacts of locking down or not locking down the nation? To consider this, it is important to consider how equity and efficiency influence each health care model.

Equity and efficiency are competing objectives when it comes to the healthcare structure of a country. To achieve high levels of equity, it is unfeasible to maintain high efficiency without blowing out the healthcare expenditure. Conversely, it is not possible to provide nationwide efficiency without reducing access of resources to some of the population. But how does this decision of priorities relate to COVID-19 outcomes? Well, it has been widely noted the success of Singapore in reducing the spread of COVID, while having one of the lowest death rates globally.1 However, does this efficiency equate to an increase in equity for the nation?

It is important to consider that in public health settings, healthcare relates not only directly to the biomedical health of the person, but also their capacity to earn and maintain wealth, as well as the social relationships they sustain. This leads to the persons’ overall utility. The task for public health is not only to consider the lives that are saved by policy efforts to limit viral spread, but also to consider the total number of lives spared and lost due to the epidemic and responses to it. Therefore, the negative effects of lockdowns must be considered analytically.2

The response of the two nations to COVID-19 couldn’t have been more different. Sweden followed a mitigation strategy focused on shielding the elderly, while minimising the disruption to education and the delivery of other health care services.3 The government provided only recommendations for social distancing, rather than mandates. Alternatively, Singapore’s focus has been to inhibit any spread of the virus. Strict tracking and tracing, quarantine measures, and lockdowns have been the mandate of the society since the outbreak arrived in 2020.3 It houses temporary facilities to admit those with mild or no symptoms, to control the spread while also leaving hospital beds for those who have more severe illness.

So why did Sweden choose to opt out of lockdowns? Well, for a country whose health system is dominated by government support and funding, it is pivotal that they maintain taxes coming in. It is, therefore, justifiable to keep an economy moving and allow for a continuation of a robust health care system. By the same token, it is important to consider that with Singapore’s very low GDP expenditure on healthcare, they can afford to increase this support even with decreases in tax contributions in the short term. Allowing them more flexibility in lockdown measures without impacting their health care economy.

Leaving your country largely unrestricted doesn’t come without risk, however, while Sweden has a higher death rate than Singapore (1.3% and 0.1%, respectively).4 Both are well below the global average of 3.2%.1,5 It is also important to note when comparing fatality rates between the two countries that while Singapore follows the criteria outlined by WHO, whereby Sweden counts fatalities as anyone who has died with COVID.2,5 Many of Sweden’s deaths came in the 80–90-year-old age bracket.4 There has been much criticism for the lacklustre shielding effort of this age group was in Sweden’s COVID response.5 It wasn’t until outbreaks started to occur in aged care facilities that masks became mandatory in such facilities.2

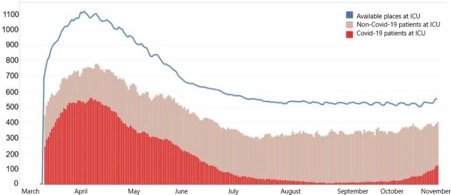

While any death is a tragedy, it is ludicrous to think that all deaths are avoidable. The same is true in the situation of COVID-19. While it has been proven possible to significantly reduce the spread of the virus by locking populations in their homes, new variants are proving more and more difficult to eliminate.6 The more achievable goal is to keep the number of infections below the maximum capacities of the national health systems. The idea of lockdowns to eliminate viral transmission is not about protecting lives in general, but only about protecting people from dying of COVID-19.2 Even during their highest peak during the pandemic last year, Sweden managed to keep well below their ICU capacity as depicted in Figure 1.2

Fig. 1. ICU capacity in Sweden, March to November 2020 (From the National Board of Health and Welfare)

Both countries provide high levels of basic healthcare, thus leading to higher levels of general health, depicted by life expectancy.1 They both also have the funding capacity to be able to increase healthcare expenditure in the short term. Therefore, both are theoretically well positioned in the defense against COVID mortality. So why did Singapore decide to go for such draconian measures? One consideration could be their poverty level. While much of Singapore’s data surrounding levels of poverty lack visibility, in 2019 the government indicated that 10-14% of Singaporean’s were characterized as living in severe poverty.7 Comparatively, Sweden has less than 1% of its population in the same category.1 Singapore has one of the largest disparities in wages globally.7 If nothing else, COVID-19 has amplified such systemic and structural inequities.2 Since social determinants of health play such a significant role in the development of severe COVID, Singapore is in less of a position to risk the spread of disease, whilst Sweden can keep the economy moving due to their lower levels of poverty in the population.8, 9

Excess mortality is an interesting point when considering healthcare equity during the pandemic. While Sweden’s overall mortality marginally increased, the same was true for Singapore.1 While Sweden’s excess can be attributed to deaths from COVID, Singapore’s cannot. Therefore, what is causing the increase in deaths during the pandemic? One theory is the implication of lockdowns on access to healthcare for other morbidities.4 Rates of outpatient care in Singapore dramatically decreased, while non-emergency surgery was put on hold during lockdowns.10 Potentially causing delayed diagnosis, leading to increased rates of death, particularly in the vulnerable.

Fig. 2. Excess mortality: deaths from all causes compared to average over previous years (from OurWorldinData.org)

So, while lockdowns decrease the number of COVID-19 deaths in a population6,9, a more sustainable perspective that balances other important outcomes and maintains the focus on public health in general without sacrificing necessary infection control measures is pivotal in sustaining equitable healthcare.

References:

Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) [Internet]. Our World in Data. 2021 [cited 3 September 2021]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/excess-mortality-covid

Kavaliunas A. Reply to a commentary on Swedish policy analysis for Covid-19. Health Policy and Technology. 2021;:100550.

Nuspatc.org. 2021 [cited 3 September 2021]. Available from: https://www.nuspatc.org/post/compare-contrast-and-covid-19-singapore-vs-sweden

Juul F, Jodal H, Barua I, Refsum E, Olsvik Ø, Helsingen L et al. Mortality in Norway and Sweden Before and After the COVID-19 Outbreak. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020;.

COVID-19 Map – Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre [Internet]. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre. 2021 [cited 3 September 2021]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

Caristia S, Ferranti M, Skrami E, Raffetti E, Pierannunzio D, Palladino R, et al. AIE working group on the evaluation of the effectiveness of lockdowns. Effect of national and local lockdowns on the control of COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. Epidemiol Prev. 2020 Sep-Dec;44(5-6 Suppl 2):60-68. English.

Philipp J, Project B, Project B, Project B. Poverty In Singapore | The Borgen Project [Internet]. The Borgen Project. 2021 [cited 3 September 2021]. Available from: https://borgenproject.org/tag/poverty-in-singapore/

Preskorn S. The 5% of the Population at High Risk for Severe COVID-19 Infection Is Identifiable and Needs to Be Taken Into Account When Reopening the Economy. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2020;26(3):219-227.

Saltman R, Yeh M, Liu Y. Can Asia provide models for tax-based European health systems? A comparative study of Singapore and Sweden. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2020;:1-18.

Singapore | Commonwealth Fund [Internet]. Commonwealthfund.org. 2021 [cited 3 September 2021]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/singapore