What is your brain function worth?

By Ebony Heins

Picture your twenties. Maybe it’s in your near future and filled with great plans, perhaps it’s in your past, good memories of being young and free from responsibility. For Sarah,* it’s her now, but it isn’t filled with freedom or dreams of the future. It involves a walker – the kind you typically see used by the elderly, almost daily uncontrolled seizures, shaking hands, and a terrible memory. Sarah’s freedom and great plans have been stolen by a crippling, and completely preventable, disability. Sarah has Epilepsy and Neurodegenerative Disease; her body just doesn’t like listening to her brain. She is 24.

It’s not the result of a large, life-changing accident, or something she was born with; it is, most likely, the long-term effects of a few small concussions. Nothing shocking or outrageous, just a few hits in soccer. The kind of thing you see every weekend at kid’s sports. Slowly, the noise around concussions is getting louder; neurologists warn us, and ex footy players stand as examples of what could happen. What we don’t see is how concussions that happen in school sports, playing on the playground, or everyday kid fun can ruin the life of an everyday person like Sarah.

You cannot talk about Australian culture without mention of football; rugby or AFL, we place these sports and their players on a pedestal. The Greats, Brownlow medallists, forever remembered in the hall of fame. Now, more and more often, these hero’s we remember are slowly losing the ability to remember us.

Shaun Smith, the man behind the mark of the century, has always been admired for his high jumps, but what goes up must come down. Smith came down, hard, easily knocked out over 12 times in his career, and has had dozens and dozens of concussions. These repeated hits have taken their toll over time, Shaun has spoken up about memory loss, increased aggression, and depression, all caused by the damage to his brain. In February 2020, Smith became the first Aussie Rules player to be diagnosed with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a condition we will discuss later, and received an unprecedented $1.4 million insurance payout.

Greg Williams is another one of the greats: the dual Brownlow medallists was praised for his courage when he sat on Channel Sevens Sunday Night and admitted he couldn’t remember his own honeymoon. He brought viewers to tears as he confessed that he regularly forgets his kids’ middle names and that most of his time playing AFL was a blur.

These football greats stand as a warning for the negative effects of repeated concussions. Together, these two men, marked as legends by their fans, have pledged to donate their brains after death to researchers studying brain damage, more specifically Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE.

How much of your time do you spend reading medical research reports? If the answer is none, you’re probably saner than me. After reading way too many reports, I became infinitely more grateful for doctors, thank god for the people who spend years of their lives studying medical jargon. We don’t need to understand the genealogical history of chickenpox or the rarer formers of cancer because we have doctors on standby to understand these things for us; to prescribe the right medication and sign our medical certificates so we can claim those three days of sick leave. We rely on them to help us through the hardest parts of our lives, but what happens when the doctors don’t understand your injury or illness?

This is where my extensive reading of medical journals took off. Dr. Bennett Omalu, a physician, forensic pathologist, and neuroscientist, researched the long-term effects of concussions for years, finding links to multiple diseases and disorders, and discovering new conditions in ex-football players. Chronic traumatic brain injury, or CTBI, is the term used to describe the long-term effects of single or repeated Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), AKA concussions. Within CTBI, you can have Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) – remember this from the former football player, Shaun Smith, there is Chronic Neurocognitive Impairment (CNI), Chronic Postconcussion Syndrome (CPS), and Posttraumatic Dementia (PTD). Although there is a known correlation between all of these disorders and concussions, there is no confirmed causation. These disorders are still in the research phase, but there is conclusive evidence of the link between concussions and some conditions you may have heard of.

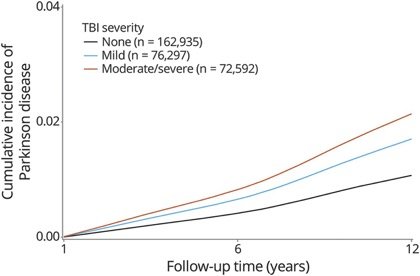

Parkinson’s disease is something associated with the elderly, but in reality, it can start in people as young as 30. It is a progressive neurological condition, wherein a neurotransmitter, dopamine, is not produced properly in the brain. Dopamine is important in controlling movement. A study by Rauel Gardener showed that people who have suffered mild TBI have a 56 percent increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, if the TBI is moderate to severe the risk increases to 83 percent. There is a proven link here, after numerous studies; what’s missing is the reason. What direct result of concussions causes this link? Dr. Raquel Gardner, assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, has been studying this link for years with no publishable results.

Image: Mild TBI and risk of Parkinson’s disease. A chronic effect of neurotrauma consortium study.

Peter* is a yacht racer, he has completed the Sydney to Hobart race multiple times in his life. A life spent in the Navy; he was constantly on boats or scuba diving around some of the world’s most famous wrecks. He was in his early 30’s when he first noticed a tremor, it happened on a boat after a dive as he fiddled with his oxygen tank. Peter has Parkinson’s disease. “When I was in school,” Peter began to reminisce as you would expect a 61-year-old to, “concussions were nothing, we didn’t even really call them concussions. We didn’t think about it because we didn’t have the information you guys have now, but you still aren’t really doing anything with it. All this;” he paused and changed his voice to a mocking tone “when I was a kid, we were tough,” another pause, this time to laugh at himself, “this crap us old people say.”

“Now we have shaky hands and bad memories so maybe we weren’t tough we were just too dumb to realise the damage we were doing.”

Image: Zane Carter

Five percent of all Epilepsy cases are caused by concussions. Epidemiologic studies by Richard Wennberg suggest that mild TBI doubles the risk for the development of post-traumatic epilepsy later in life. Seizures could develop straight after a concussion, or years later, and there is no way of knowing who will develop Epilepsy. There are some studies that suggest there is a genetic predisposition for Epilepsy, this doesn’t mean you will certainly develop it, but it means that a concussion can push you over the edge.

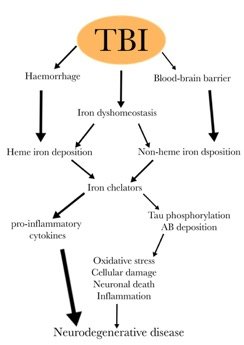

Neurodegenerative disease is the product of brain damage that slowly breaks down different functions. Concussions can cause iron dyshomeostasis, blood-brain barrier breakdown and haemorrhage. Dr Maria Dagla from the Flory Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health has linked these to oxidative stress, neuronal death, inflammation and tau phosphorylation. Combined, these ultimately results in neurological decline and an increased risk of developing neurodegenerative disease.

Source: Curieux

10th of September, 11:04am, my phone goes off, it’s a text from Sarah, I haven’t heard from her in over a week.

“Hi eb sorry I’ve been ignoring u I wont really be able to talk to u anymore. I had a big seizure and I’m back in the hospital and mum thinks its too stressful to talk about everything. I really hope u got everything u need and good luck writing your story but I don’t want to read it but maybe one day I will.”

This is Sarah’s story.

In 2010, Sarah was a fierce 15-year-old finishing high school. She regularly got in trouble for breaching the uniform code and once ditched English to watch an interschool boys’ soccer game. She called herself a ‘soccer girl,’ she represented the school and played for her local club; and she was pretty good – at least that’s what she tells me. “Not good enough to play professionally or anything, but certainly the best on my school team,” she didn’t say this in a cocky way, it was pride, mixed with melancholy.

Talking to Sarah was always a roll of the dice, some days she would seem so normal; talking about friends and studying, other times she sounded almost broken.

This role of the dice doesn’t just control how she sounds, it controls her body; “it’s like my body is a really old computer, sometimes when I turn it on it works fine, it’s slow and makes funny sounds but still, it works,” she laughed at her own analogy, “[other times] it doesn’t matter how many times you turn it off and on again or kick it or yell at it or give it new drugs it just won’t work because the truth is it’s broken.” She said this with a sort of pale acceptance which continues as she described her daily struggles: “I can write for about 20 minutes before my hands start shaking, and maybe 30- or 40-minutes typing, sometimes I’ll record myself speaking my essays instead of typing them but when I listen back, they are always terrible!”

Sarah often says things that are sad with a harsh mockery, like she is making fun of her disability as a separate being from herself. Maybe she is saying how stupid her coping mechanisms are, or maybe she is saying how stupid it is that she needs them.

“You always see sick people who are super happy, like ridiculously happy guys in wheelchairs playing basketball or a sick kid in hospital laughing with their happy family around them and honestly it’s crap. I’m not your [..] inspiration porn so if you don’t care when I’m angry you shouldn’t care when I’m happy. I’m pissed. I want to scream every time I have a seizure or can’t hold a pen; I want to slap people who look at me like a lost puppy […and] I want to go back in time and tell my teachers that they did this. They were supposed to look after me but when I had my concussions, they let me keep playing, they sent me straight back on the field [after getting concussed]. I wanted to, but I was a kid and they were meant to look out for me. It’s not like this is their fault, but they screwed up and while I have to live with it every day, they don’t even know what they did was wrong.”

That’s Sarah’s life. No pretty pictures of her smiling despite her disability and no hiding the anger she feels. Her life is something we don’t imagine for ourselves; Peter’s life is something we accept may happen: but what if we could avoid them both? Should we stop everyone under 18 from playing contact sport as Dr. Bennett Omalu suggests? We have more knowledge now than we have ever had before, we can see the medical effects of concussions, and yet in Australia children as young as 12 play contact sport. Accidents happen every day; we can’t stop kids from getting concussions, but we can lower the risk of long-term effects. We can use the knowledge we have that Peter’s generation had to go without, and we can do better than Sarah’s teachers. We can look after our kids because sometimes; being tough is dangerous.

*Peter and Sarah’s names have been changed to respect their privacy.